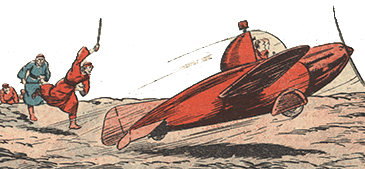

"Wonderwings" – adapted from Sparkler of 28 August 1937

One of the earliest Victorian juvenile periodicals promised its boy readers “wild and wonderful fiction” (Boys of England, 24 December 1866), and, indeed, adventure stories have been a staple ingredient of British children’s literature since the mid-nineteenth century. This makes it all the more puzzling that for many years the adventure strip or “dramatic picture-story” was evidently not regarded by comics publishers as a genre to be promoted. When Alfred Harmsworth embarked on his campaign to capture the market for comic papers in the 1890s, he decided that small-print letterpress adventure serials and stories had to be essential ingredients in the recipe, but had to be kept separate from the comic strips. In 1898, for instance, Chips consisted of (approximately) 50% comic strips and cartoons plus 50% small-print adventure fiction, including the text fiction “The Smuggler of St. Ormes”, The Fatal Seven” and “In the Land of Mysteries” (Illustrated Chips, 1 October 1898). For many years these two sections in the comics, “Screaming Sketches, Engrossing Tales” (masthead of The Comic Home Journal, 1902) or inversely “The Best Stories and the Funniest Pictures” (masthead of Illustrated Chips, 1922), remained separate and distinct. Perhaps this clear compartmentalization into serious fiction here, humorous comic strip there, is one of the reasons why the adventure strip was slow to enter and then develop in British comics.

There was one early false start. “The Scouts of the Wild Cat Patrol”, a page-one adventure strip signed “S.H.” (an unidentified artist), ran in Comic Life in 1910, only to be handed over after a few weeks to Harry O’Neill and converted into a humorous strip, “The Red Lion Scouts”. And then there were several “domestic strips” for younger children in their comics, tots’ thrillers featuring foundlings and orphans with names like Little Nell, Tiny Tom, Poor Peggy, and Lonely Dan. However, the clearest date for the beginning of the British adventure strip has to be 15 May 1920, when Walter Booth’s pioneering “Rob the Rover” commenced in Puck, running there until 11 May 1940 (Gifford 1984: 66). Booth’s young hero begins his adventures in time-honoured fashion as a castaway on a desert island, but is soon rescued by an old sailor, Dan, so that his real adventures can begin: in jungles and lost cities throughout the Empire; on ships, airplanes, and finally on board a flying submarine. “Rob the Rover” quickly became a popular and attractive, red-and-black strip, and yet during the full 21-year series, Rob was never given the distinction of being placed on the prestigious cover page of Puck – the front page of a comic had to be, well, comic. Inside Puck, however, there had been steady changes, and by 1931 it was running four adventure strips.

The 1930s was the decade when the British adventure strip spread and matured. Adventure strips were introduced into the knockabout comics, and a threesome of new weeklies appeared that despite their allegiance to the traditional British comics format can legitimately be called the first British adventure comics: Jingles, Sparkler and Tip Top (all commencing in 1934). There were plenty of competent adventure-strip artists working in this decade, and yet their artwork seems to have been hampered by old comic-strip conventions. For a long time there was something awkward about their adventure material, in the use of speech balloons, the linking of panels, the presentation of character, movement and action. And then those small-print captions, some extending to ten lines, on occasions up to a thousand words or more per page, which often seemed to offer a different “voice” and a different interpretation of the action portrayed in the panels printed immediately above them. Neither smooth nor coordinated, such artwork often seemed cramped and static, until the innovative Reg Perrott – again in Puck – reduced the number of panels and their shape, using shifts in point of view, and introduced hand-lettering into the clipped and functional captions. And finally, in the London-based Mickey Mouse Weekly (1936 on) and its competitor Happy Days (1938), in the work of both Booth and Perrott, full colour came to be integrated into the British adventure strip.